The Logbook method of designer performance management

I mentioned a couple of weeks ago my belief that observation-driven performance management processes do designers a particular type of disservice in typical tech organisations. I also mentioned that I had a developing thought on what a good alternative might be. Today I’m going to expand on that a little and invite you to think this through with me.

At the core of my complaint with this type of performance management processes is that it relies on observations typically drawn from people who have too few of them and who are under-qualified to make them because they often aren’t designers and therefore lack the depth and breadth of understanding with which to contextualise their already thin perspective. This is not a criticism of those people, but of the process which asks cross-disciplinary and often non-technical peers to weigh in on a role which is still poorly understood in almost all businesses. We would be - and I’m sure are - equally lacking when giving input on the performance of sales managers, operations teams, marketeers and data scientists.

In a LinkedIn post pointing to my previous article, my friend Andy Budd summed this up nicely:

One of the biggest frustrations I hear from designers I coach is being held accountable for the business success of a feature they had little say in shaping. Maybe they flagged issues early, pushed for improvements that never landed, or had to quietly execute a flawed idea. But come review time, they're still measured by the outcome.

The result? Performance evaluations often feel like a lottery — heavily influenced by the project you were assigned, the strength of your peers, and whether your PM liked working with you.

Andy goes on to suggest designers keep a Brag Document, and this is pretty much where I have ended up in my thinking on this topic, albeit with a more functional and hopefully easier to sell name - the Logbook.

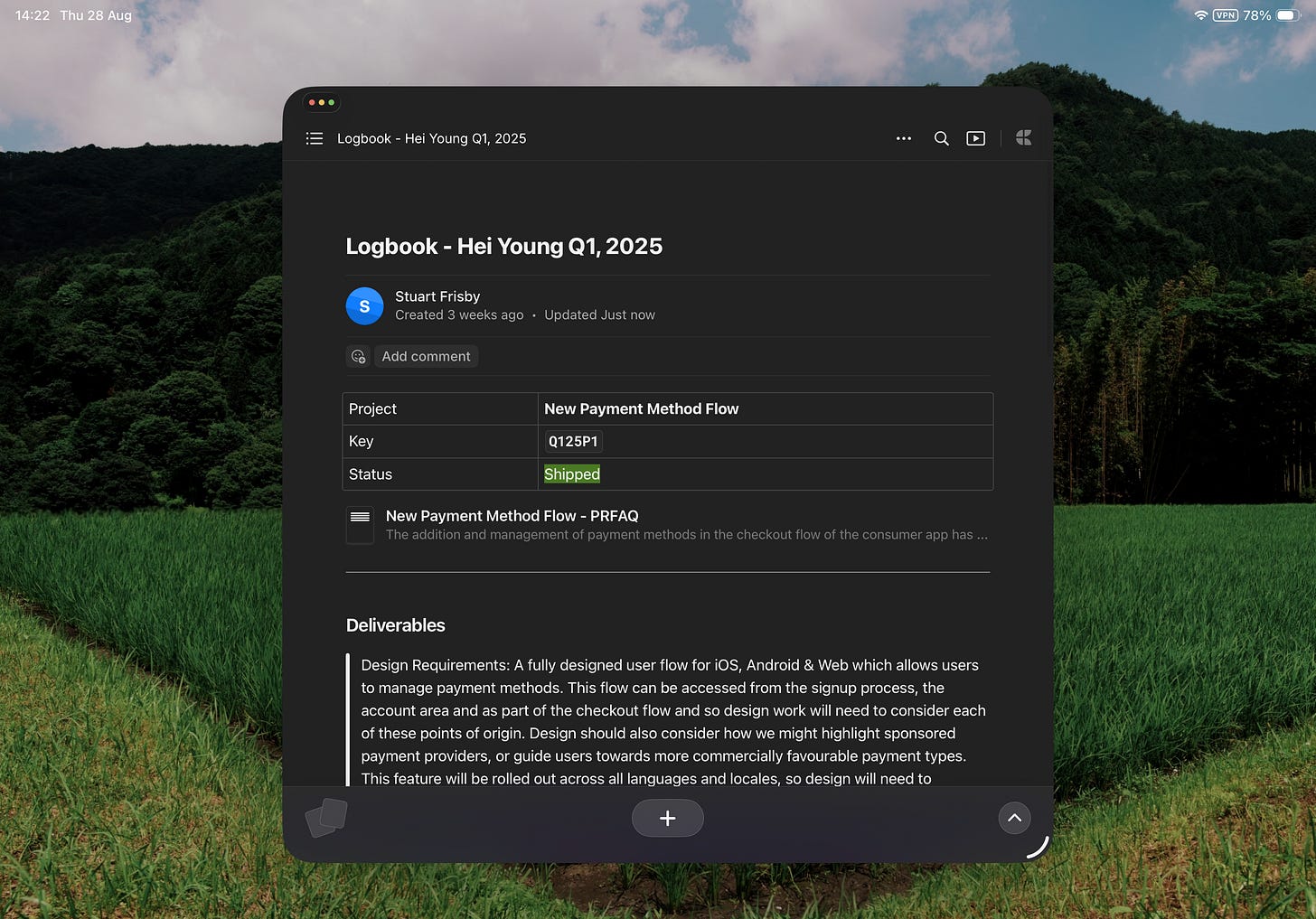

The logbook format is a simple way for designers and their managers to keep a running record of everything a designer has worked on, such that come the end of the performance period there is a readymade document to use to guide, inform and steer the debate on performance which comes from performance calibration sessions. The logbook does a couple of things which I think are valuable:

It provides the context for the work - the business problem being solved, and crucially the articulation of that problem from a Product Manager in the form of a hypothesis or a PRFAQ.

It ask for specific feedback from peers in real-time on the aspects of the work which they are qualified to weigh in on. An engineers will be asked about the implementability of the design work, a data scientist will weigh in on the measurability of the design work and the business outcomes attached to it. Product managers will talk about that business impact and the role design played in achieving it.

This targeted form of feedback avoids the tendency I have seen in these processes for people to make broad generalisations based on narrow datasets, and instead embraces the narrowness of the collaboration by going deeper on the impact of the work.

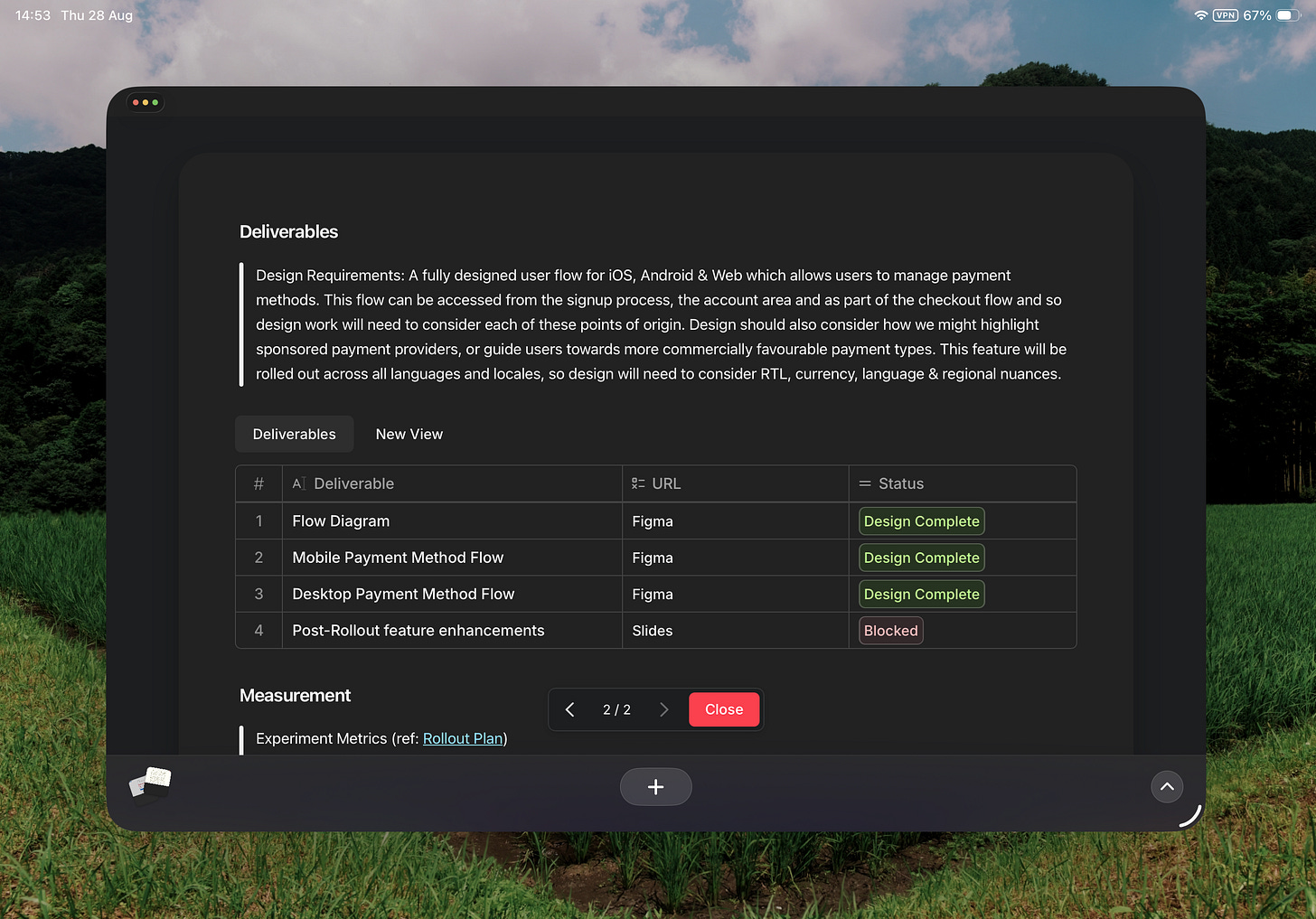

The logbook also includes a list of deliverables which the designer created, not just the end-state of the work which may or may not have gone live, but the thinking, the synthesis, the exploration, the version the designer considered the MVP, the version which was subsequently shipped as the MVP, the fast-follow, the long-term vision, etc, etc. This shows the work, not just the tip of the iceberg which we are typically showing peers through other processes.

Come the end of performance period, the manager has a list of logbook entries which:

Cumulatively represent the total impact of the designer

Describes feedback from a broad range of informed stakeholders

Includes work which goes beyond the superficial

This document is - in the aggregate - therefore a much more robust reference to take into a performance management process which is likely under pressure to conform to population bell curves, stack ranks, and budgetary constraints, all of which apply downwards pressure which is disproportionately felt by our discipline and others like it.

In that process a manager then has the opportunity to share the logbook, and ask for input on it, not on performance in the abstract based solely on broad and shallow 360 feedback. Reassured by the thoroughness, specificity and representativeness of the feedback, I think it’ll be easier for design managers to prove performance this way than it is with anecdotal, opinion-driven, low-quality observations drawn from a distance. This process also allows designers to feel some greater sense of control over their own destiny. They should have a pretty solid grasp of where they stand by themselves looking at the logbook and the feedback therein, and the most proactive amongst them may even look for in-period opportunities to course correct and show a willingness to improve upon emerging areas of development.

If there is one single sentence summary of this newsletter so far it is that design and designers are not like product managers and engineers, and the sooner we stop treating them as such, the better it will be all round. This is one of the processes where I sense we are most lacking in bespoke tools, and most in need of them.

What do you think? Would a logbook-driven performance management process work in your organisation? Does it solve the pitfalls I outlined above or perhaps introduce new ones? I’d love to get your thought on this and to develop my thinking on it with your input.

Just a quick note here to say hello and thank you to all of the folks who have recently subscribed to this newsletter. It’s both super energising and mildly panic inducing to see the calibre of people who are entrusting me with a slice of their inbox. If there are particular topics you’re interested in hearing about, or areas you think would be fun for us to explore together, do let me know.

Thanks,

Stuart.

Love this concept, thanks for sharing. I much prefer the framing of 'log' over 'brag' - particularly to help non-design folks understand the value of this process.